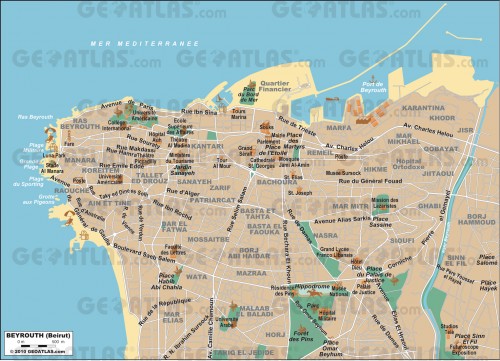

This is Beirut.

Beirut.

Soon after I left Belfast in 1991 I met a guy in a bar. Both avid travelers, we talked about where we wanted to go next.

“Beirut”, I said, “in Belfast I learned that people live lives and the media writes stories mainly to make money. The difference between those realities is fascinating”.

He shook his head, “You’re crazy, lady”.

“Not at all. I’ve done Belfast. I just need to visit Beirut and Belgrade and then I’ll be done. I want to know if we’re all being duped by newspaper headlines”.

Then I fell for him. We got married, had kids, traveled a fair bit but I never got to Beirut – until this year. My friend Karin was there interning with the UNHCR. We chatted, me at my desk in Google Seattle, her in her little hostel room in Beirut.

“Come over. It’s amazing. You’ll love it.”

The local, national and international news were full of reports of the war in Syria. Journalists filed stories about the war and tensions in neighboring countries including Lebanon and Jordan “from Antakya” or “from Beirut”.

“Is it safe?” I asked Karin, the words feeling like something someone else would say even as they came out of my mouth.

“Totally. It’ll be great.”

She had been there almost three months. Convinced that an opportunity like this doesn’t come every day I booked flights.

Days later the papers were full of bombings in Tripoli. Oh well, too late now.

I lined up at passport control at Beirut airport with a hastily completed visa form in hand betting on a lackadaisical border guard. The form was pretty specific: in return for generously providing visas on demand at ports of entry, the Lebanese government asked travelers to provide a local address and phone number. Not an outrageous demand by any stretch, simply complicated by me totally forgetting to ask Karin for her address – and my phone was dead so I couldn’t even call her.

The border guard wasn’t impressed. I was curtly and dismissively escorted into a small room populated by a bunch of equally stern and forbidding-looking (armed) guards. My escort deposited me and disappeared back to his post with no explanation.

Lovely. When in doubt, play the girl card…

“I’m so sorry. I’m such a ditz. My phone is dead…”

The officer in charge looked as me with about as much respect as if I’d crawled out from behind the dingy battered sofa in his drab, industrial, grey office.

“My friend, I’ll be staying with her but I don’t have her address…”

He held an old-style telephone receiver in hand. His stare bellowed “Lady, can’t you see I’m busy? You wait until I’m ready for you!!”.

I persisted in my friendliest voice “I just need to charge up my phone and then I can call my friend…”

Now he really couldn’t believe my impudence. He gestured to a junior guard who beckoned me out the door and pointed out a power socket on the wall – still on the wrong side of the border checkpoint.

I thanked him profusely and rummaged in my bag for socket converters and power cords.

Five minutes later my phone had a smidgen of charge, enough for me to open my email. I had to lean across the barrier marking “no-man’s-airport-land” and Lebanon to connect to the airport free wifi. There was no-one left at the border checkpoints except a couple of bored guards who stared at me as I leaned over the barrier shamelessly, an internet hussy. I smiled back.

Karin’s phone number in hand I marched back into the office waving my visa form out in front of me. The officer was possibly less happy to see me than the first time, now he had to actually deal with me. Thankfully, a couple of quick phone calls later the form was filled out to his satisfaction, my passport stamped and I was on my way – and I knew that Karin hadn’t given up on me and was waiting in arrivals.

Later that evening Karin took me on a walk along the Corniche in central Beirut. From her hostel in Ain el Mreisse just below the American University we walked along the water, past the upscale yacht club all the way to Martyr’s Square and then through the eerily remodeled souk area to Place de L’Etoile.

Corniche comes from the french word for ledge, usually used to describe a road on the side of a cliff or a mountain with the ground falling away from the road on one side and rising on the other. The lower part of the Corniche in Beirut, the part that we walked, felt much more like an Esplanade, a broad generous path full of Beirutis enjoying the summer evening.

“Color” is the single word that pops into my mind as I recall that walk. Maybe it was the summer evening sunshine or maybe it was the light reflecting on the Mediterranean. My first impressions of Beirut from that evening are peopled with groups of young men smiling and calling out to us cheerfully as we passed, young families, rambunctious children and girls wearing headscarves in every color but black.

On the streets of Tehran, the sea of black chadors felt to me like a surprise slap in the face. The absence of color hurt my eyes and my heart. Even though I know that Lebanon has a large Christian community, it is a predominantly Muslim country. Subconsciously I arrived in Beirut expecting Tehran. The riot of brightly-colored headscarves with matching shoes and bags or a headscarf complimenting a gaily patterned top made me practically giddy and lifted a weight I hadn’t realized I was carrying. The Corniche that evening was, for me, a rainbow of bright, strong colors and it made me want to laugh out loud.

The Corniche is also the Avenue de Paris and on the Avenue de Paris the true heart of Beirut calls in honking horns, drivers barely observing lane markings and treating traffic signals as nothing more than a suggestion. Vibrancy of an entirely different kind. It was traffic like I’ve never experienced before. It made Hanoi and Beijing with their schools of motorcycles seem positively pedestrian. Traffic in Lima or Rio can be navigated fairly successfully if the driver remembers to look only ahead and move quickly – at least there cars on the left drive left and cars on the right drive right. In Beirut such directional obeisance is noticeably absent. It’s chaotic and raucous but strangely, it works.

At the far end of the Corniche we nodded at security guards and passed into another world. Like a World Showcase in Disney’s Epcot the Zaitunay Bay area is the Middle East re-imagined. It could be Vegas or Sydney or the South of France. The restaurants are modern, the yachts new and extravagant, the ambiance exclusive. To walk into this area on the turn of a corner was bizarre and almost disappointing, “I thought I came to Beirut, where is this place?”. Thankfully the cacophony of car horns was still audible.

We walked through Zaitunay Bay and out the other side where the Corniche is no more and instead we needed to cross a four-lane highway on our way to up Martyr’s Square. For the second time that evening I felt the dissonance of Beirut’s post-war recovery acutely. Where the marina area is ultra-modern, Martyr’s Square is a historical landmark. The Martyr’s statue in the center of the square is bullet-riddled. Beirut yesterday, meet Beirut tomorrow.

The shell of a planetarium stands, like a skeleton on one side of the square all rubble and bare concrete bones. The Mohammad Al-Amin Mosque, domes in glistening blue tile with a gentle twilight glow on the yellowed stones, in the background. Lebanon old and new? I wish I could say. Planetariums obviously, are like orthodontia, nice to have but nowhere near as necessary as a functioning place of worship.

By now I was flagging, feeling my jet-lag in every step. We passed the Roman Baths and I barely noticed (!!). We walked down the new pedestrianized streets toward Place de L’Etoile and the fruity smell of flavored hookah was overpowering and nauseating. My treat for the evening was a silver moon over the brilliant domes of the mosque visible behind St Georges Greek Orthodox Cathedral. OK so the current cathedral building is fairly new but the original church dates from 400 A.D. This, this layering of history and culture, this is the Beirut I’d come to experience and try, meagerly, to understand.

Related Posts

[catlist tags=Lebanon]